Fact Checking Biden's CNN Town Hall

Published: Apr 20, 2020 3:02:17 PM

“When journalists learn things they think are important, to not publish is a political act, it’s not a journalistic act. When journalists learn things they think are important, there should not be much which is learned which is not published. Publishing is journalism; not publishing is political balancing.”

On March 25, Tara Reade, who spent 9 months working in the Senate Office of the presumptive Democratic Presidential Nominee Joe Biden, took part in a podcast interview in which she alleged that Biden had assaulted her in 1993. The interview itself, conducted by writer and broadcaster Katie Halper, is extremely detailed and comprehensive; covering Reade’s time working for the then Senator for Delaware, her account of the alleged harassment and later assault, her difficulties attempting to report them at the time, and later in trying to come forward with her story. Reade claims that Biden touched and stroked her on several occasions, asked her to serve drinks at a function because of her physical appearance, and on a separate occasion pushed her against a wall, reached under her clothes and penetrated her with his fingers.

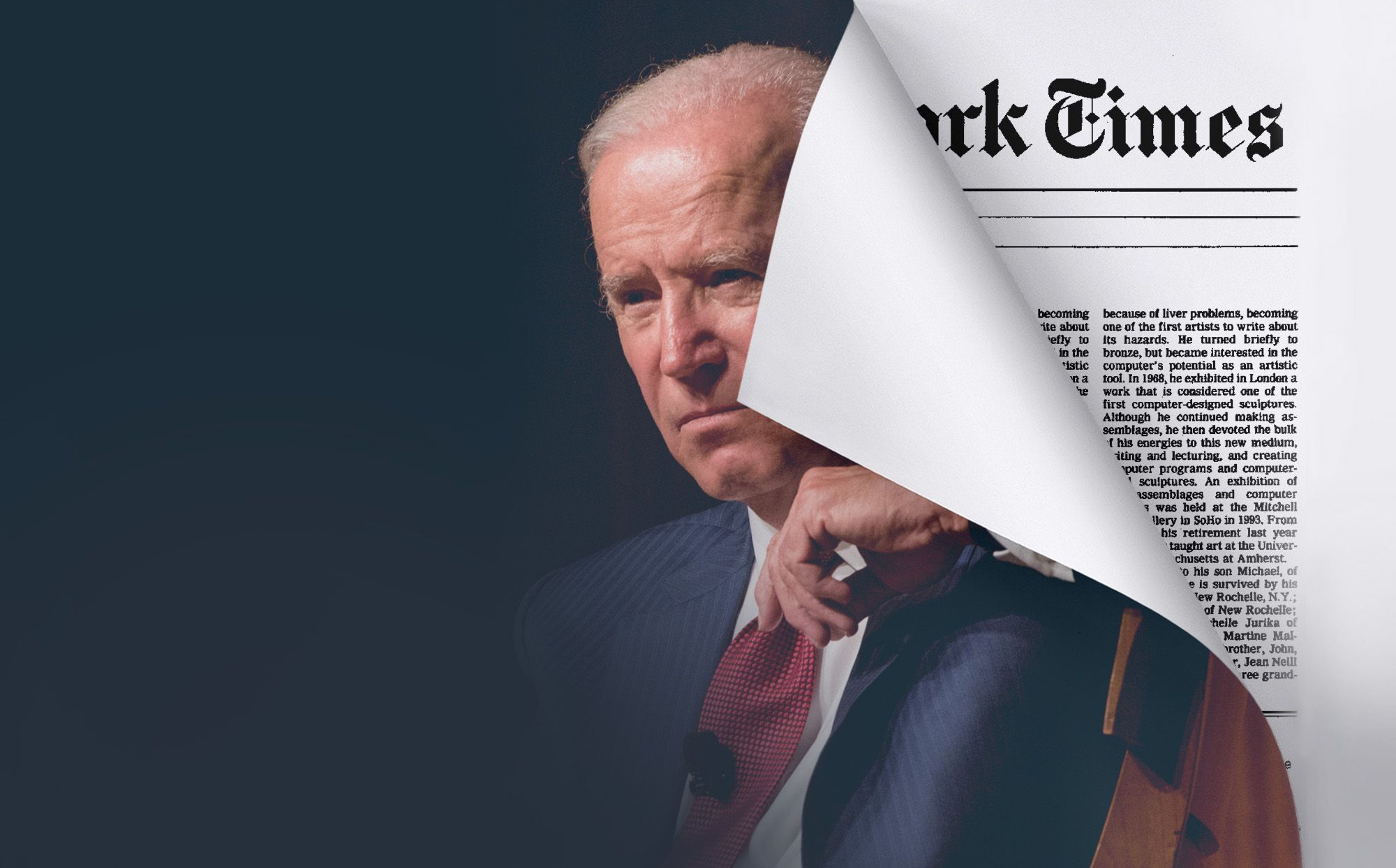

When Ms Reade made the accusation, the response from the national media was conspicuously slow. A search for references to the story from the days following the accusation shows that Chinese, Spanish and Polish media were quicker to report on the story than most big US broadsheets. In particular, the New York Times did not report on Reade’s allegations until April 12, a full 19 days after they were first made public. This raised questions on social media and in other outlets across the political spectrum about the New York Times’s consistency, or perhaps lack thereof, in handling accusations of assault made against politicians of different political persuasions. The Times’s response is of particular interest in this case, as they have been praised as a leading outlet for breaking and handling these kinds of stories since the inception of the #MeToo movement, beginning with assault and rape accusations against Harvey Weinstein in October 2017.

The day after the Times first published the story of Reade’s allegations against Biden, the Times’s media columnist Ben Smith took his own paper to task on the delay in reporting. Smith published an interview with the executive editor Dean Baquet in which Baquet addressed the questions around the Times’s editorial decisions in this case. Smith’s questioning is incisive; as far as the Times’s reputation goes, perhaps too incisive, as it serves in several cases to highlight the weakness of Baquet’s justifications.

Baquet’s first claim is that the Times did not report it as breaking news because: “Lots of [outlets] covered it as breaking news at the time. And I just thought that nobody other than The Intercept was actually doing the reporting to help people figure out what to make of it.” Unfortunately for Baquet, this is simply not true. The Intercept was almost alone in its coverage at the outset; the Washington Post also did not cover the story until the Easter weekend, when the Times’s first coverage was published. On the day Reade went public, CNN did not mention her allegation but did run an analysis segment with Chris Cillizza on the subject of Biden’s gender politics (discussing which of ten possible female candidates Biden might pick as his running mate). The Guardian US made the slightly odd decision of not breaking the story as news, but two days later published an Opinion piece by Arwa Mahdawi commenting on the media’s failure to cover the story.

To return to Dean Baquet’s answer however, even if it had been the case that many other media outlets were covering the story, standard journalistic norms do not dictate that in an election year, there is no need for a major news outlet to cover a serious allegation against a presumptive presidential candidate, simply because ‘other people are doing it.’ If it is to honor its status as the paper of record, the Times must accept two premises: the first is that it has the responsibility to maintain a complete record of the news, in as timely a fashion as is possible. The second is that it is simply not true to claim, when convenient, that the Times is only one voice among many, and if other outlets cover a story then it ceases to be relevant to intervene.

The second part of Baquet’s justification centres around a comparison with the Times’s coverage of the assault allegations levelled against the then Supreme Court Nominee, now confirmed Justice, Brett M. Kavanaugh. Asked if he felt the approach to the two instances differed, Baquet gives the following response: “Kavanaugh was already in a public forum in a large way. Kavanaugh’s status as a Supreme Court justice was in question because of a very serious allegation. And when I say in a public way, I don’t mean in the public way of Tara Reade’s. If you ask the average person in America, they didn’t know about the Tara Reade case.”

This answer appears both confused and confusing. Baquet seems to be comparing Kavanaugh’s public status with Tara Reade’s, rather than with his obvious analogue here: Joe Biden. The factor which determines the importance of the allegation is not of the prior prominence or status of the accuser, but of the accused. The blurred comparison here comes off as rhetorical sleight of hand, designed to shift the focus from Biden to his accuser. At the same time, Baquet is shirking responsibility here, for the power that media has to create public awareness, rather than simply relate things about which the public are already aware. At the time of the allegations against Kavanaugh, his accuser Christine Blasey Ford was also unknown outside of the world of academic psychology. The Times itself contributed to the media frenzy which catapulted her into the public eye, publishing hundreds of articles, both news and opinion, about her allegations. With no further justification given for the difference in treatment between Blasey Ford and Reade, or of Kavanaugh and Biden, it is difficult not to interpret this justification as deeply cynical.

Baquet also suggests that doubt as to whether Ms Reade’s allegations were credible influenced the decision not to report. Regardless of what appropriate journalistic standards are when it comes to reporting sexual assault allegations against prominent figures, Baquet’s justification here again falls flat when compared with the Times’s treatment of the Kavanaugh case. Another accuser, Julie Swetnick, claimed to have witnessed Kavanaugh participating in abusive behaviour at parties where women were “drugged” and “gang-raped,” though she stopped short of accusing him of molesting her personally. Parts of the accusation were later walked back, and ultimately Swetnick’s testimony was not brought before the Senate Judiciary Committee, unlike Blasey Ford’s. Despite these later developments, on the day that Swetnick came forward the Times covered her allegation, admitting that: “none of Ms. Swetnick’s claims could be independently corroborated.” It seems the Times has previously had no problem covering allegations without being able to fully corroborate them, with appropriate caveats included in the story, so why the different standard for Tara Reade?

Hindsight is 20/20, but no editor, however talented or honest, can possibly know how credible an accusation such as these will turn out to be, that’s why the accusation is itself the news. Here at Logically we specialise in fact checking, and arguably the only responsible way to fact check allegations of misconduct is to focus on the fact of the allegation itself. Evidence can be weighed; other contemporaneous accounts may or may not corroborate an accusation. In the years since the start of the #MeToo era, we may even feel bound by an ethical injunction to believe women who accuse men of assault in close to all cases, as a means of acknowledging and redressing structural damage, but the fact that a woman came forward and made these claims is in itself indisputable.

Reasonable people can certainly disagree about what the appropriate journalistic standards are in reporting stories such as these. What reasonable people should not disagree about is that these standards, once adopted, should be held to in a transparent and accountable fashion. Not everybody would agree with the concept of journalistic duty outlined there, but we would hope that an editor, having committed to that line, would stick to it. The quote that opens this article is from Dean Baquet himself in an interview with the Times’s Daily podcast, (listen from 26 minutes in if you want to check) defending the Times’s reporting on the Hilary Clinton email pseudo-scandal. That interview aired on the 31st of January this year, just seven short weeks before Tara Reade went public with her allegation, only to be met with silence from the press.

By Baquet’s own analysis then, the choice not to publish the story that was made day after day up until the 12th of April, simply must be recognised as a political one, from which Joe Biden and his team certainly benefited. When Baquet speaks on behalf of the Times, he acts as a figurehead for a paper that claims to be a bastion of reason, civil discourse and high journalistic standards. To make such a claim and then act with the kind of inconsistency on display here at best leaves the Times’s editorial board open to a charge of hypocrisy, and at worst betrays an institutional malaise which threatens to undermine the organization as a whole, and what it claims to stand for.

The Times’s motto is “All the news that’s fit to print”: there follows the implication that if they do not cover a story it wasn’t news, or that it wasn’t fit to print. In the case of Tara Reade’s allegation, that should concern, if not outrage us.

Last month, after concerns about voter safety were raised amid the coronavirus pandemic, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order postponing the New York primary from April 28 to June 23. With currently over a quarter of the country’s...

Get the latest fact checks, exclusive content and keep up to date with how Logically are fighting misinformation.

Copied!