Every day this past week, I have been woken up in the UK at around 5:30 am – either by the baby, or by my body clock, which said baby has been violently tampering with – and checked the news from the US on my phone.

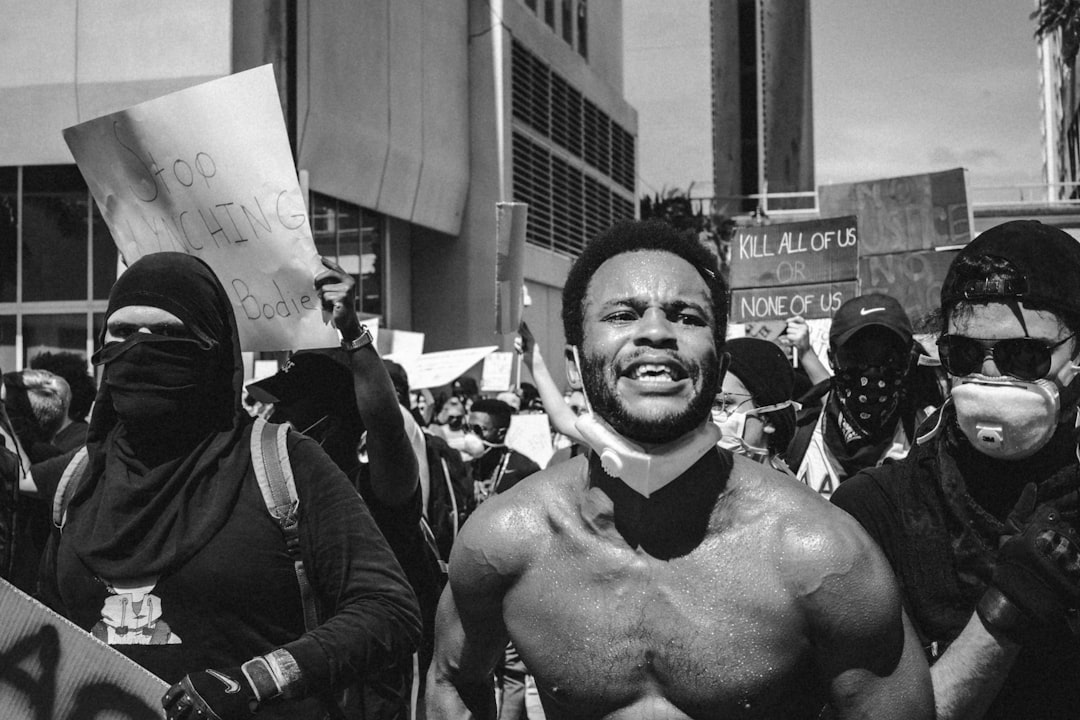

What I receive is a great blur of information, arranged by live blogs and algorithmic social media feeds into an unhelpfully inconsistent chronology, from a range of sources: mostly news websites like The Guardian and The New York Times, and videos and eyewitness reports I see shared on Twitter by citizens “on the ground.” Reports of protests, riots, and police violence; of curfews enforced and precincts burning down. Journalists being shot at by cops armed with rubber bullets, police driving cars into crowds. Heavy-handed gestures of solidarity by massive corporations; the president hiding in a bunker in the White House like he’s cosplaying the last days of the Third Reich, getting himself censored by the social media corporation he first built his base from as he threatens to escalate the violence. The US is in meltdown – the world’s richest and most powerful nation could well be experiencing a crisis of legitimacy analogous to the one which precipitated the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 90s. With this, a large chunk of the assumptions which undergird mainstream political reporting are being foisted right out the window.

How can I – how can anyone – keep proper track of what is going on right now? Probably the main way in which I am following the protests is through social media. But here I am immediately presented with a number of difficulties. I’ve already mentioned the chronology: since I live across the Atlantic Ocean, I am asleep when most of the key events are happening. This means that by the time I am able to absorb them, they have become an uneven bricolage of reports of protests beginning, escalating, being dispersed, etc. – with little approximation of how they might have occurred in real time.

This problem is compounded by the fact that America itself exists on a number of time zones, and the protests are happening all across it (events to demand justice for George Floyd have been held, by now, in all 50 states): by the time I wake up, what is happening in Washington and New York may be mostly over for the night, but in Portland or LA it could still be building up to a peak. A lot of the relevant information may only trickle into my social media feed a day or so later, as videos of police violence shared by small accounts take a while to build up enough momentum to appear on my timeline. The familiar ‘social media bubble’ problem also applies here – I tend to only see things that people I follow are interested in as well. My feed is full of videos of police violence – but other people might see content focused on reports of looting, or of protests being escalated by ‘anarchists’ coming in ‘from out of town’ (this notion, perhaps unsurprisingly, turned out to be fiction).

Meanwhile, understanding what I am seeing on social media requires a great deal of context – which may not be immediately available. This problem seems especially tricky if, like me, you are following what is going on as an outsider: someone who is not American, and has never lived in the US. Understanding what is going on requires a knowledge of things like the geography of US cities – what sort of people are assumed to live in what neighborhood; where these neighborhoods are in relation to everything else; how the places people are gathering are laid out. You need to know things like the difference between the police, military police, and National Guard – and when it is and is not constitutional for security services who are not the police to be deployed. You need to understand at least some of the general facts about the way that the police in the US are funded and equipped, and about the history of violence by the police towards minority communities, especially African Americans – earlier unrest like Ferguson, and the LA riots. Some of this information can be built up passively, through context clues, or might be provided by the deeper, more considered threads which typically follow waves of urgent video reportage – but a lot of it will require a degree of effort I may well (as an outside observer, with my own more direct and local commitments) struggle to bring to bear.

Large media institutions, of course, could help. Twitter, for example, has (infamously) started annotating certain tweets. But the platform is unable, I think just formally, to provide anything like the information that would be needed: to furnish all users with the deep background understanding that events now demand, Twitter would need to change the way it functions quite profoundly. Perhaps this is where more established, mainstream news outlets can help – op-ed journalism, in particular, is able to justify its existence by providing readers with this sort of background. While much of the coverage of the protests has been through live blogs – which are subject to similar, if less intense, problems as algorithmic social media feeds, with certain stories or perspectives getting buried and then lost to time – the expert perspective of journalists might reasonably be assumed to be helpful. But here we have reason to be suspicious too.

The news, like any intellectual activity, is built on a theory – or set of theories. Reporting the news involves making sense of how one event is linked causally to others; it involves the assigning of motive, and responsibility. Certain actors will thus be seen as more or less trustworthy, or in the right; certain ideals will be seen as inherently worth upholding. The vast majority of US news outlets have, until very recently at any rate, assumed that the police are more trustworthy than the people they are policing; assumed that the institutions of American government are, overall, good and worth upholding. There has long been reason to be suspicious of this – but now these reasons must be obvious to all but the most biased and blinkered observer. It is impossible to provide neutral reporting of factional violence between the police and (a substantial portion of) the populace, if one always defaults – whether consciously or otherwise – to always being pro-police. Thus, while traditional media coverage of the protests might be able to provide more extensive and immediate context than something like Twitter, this context might in truth be more distorting than it is illuminating.

An object lesson in this was provided on Wednesday, when the New York Times chose to publish an op-ed by the far-right US senator Tom Cotton, calling on the military to be brought in to quash the protests. To the editorial board, this falls within the range of perspectives it is necessary to consider; to others, it looks like the paper is needlessly platforming a politician calling on the state to use military violence against its own citizens.

All of this, I think, serves to emphasize the importance of what the philosopher Max Horkheimer teaches us in his 1937 essay ‘Traditional and Critical Theory’ – which functioned as a sort of manifesto for the school of Frankfurt School Critical Theory Horkheimer helped found. ‘Theory’, for Horkheimer, can be defined as “the sum total of propositions about a subject” – knowledge in the most general sense. For the ‘traditional’ theorist, these propositions are “so linked with each other that a few are basic and the rest derive from these. The smaller the number of primary principles in comparison with the derivations, the more perfect the theory.” But: “the real validity of the theory depends on the derived propositions being consonant with the actual facts. If experience and theory contradict each other, one of the two must be re-examined.”

‘Traditional theory’ thus aims at what we would perhaps call ‘objective knowledge’ – “the closest possible description of the facts,” embracing “all possible objects” but independent of any particular observer. In a sense then, the role ‘traditional theory’ plays in Horkheimer’s argument can be considered analogous to the sort of ‘balanced’ coverage of events aimed at by media organizations like the NYT and the BBC – where the truth is always assumed to lie somehow between competing political extremes.

But for Horkheimer, while this sort of neutrality might to an extent be appropriate for the natural sciences, when it comes to understanding human-level things (“the sciences of man and society”), it is always necessarily misplaced. No social scientist (or journalist, or activist, or someone watching events unfold on social media) is able to stand detached from the society they are attempting to understand: “the scholar and his science are incorporated into the apparatus of society; his achievements are a factor in the conservation and continuous renewal of the existing state of affairs, no matter what fine names he gives to what he does.” This involves a sort of “false consciousness”: by insisting on their own neutrality, the traditional theorist lets various biases creep in – Horkheimer is particularly concerned here about biases which inadvertently benefit the status quo. Traditional theorists take too much for granted, failing to investigate the foundations on which their most basic theoretical propositions rest (here the analogy might be something like a journalist insufficiently critical of the role of the police – thus credulous with regards to how the police relate events).

Thus Horkheimer recommends embracing what he calls ‘critical theory’ – defined as a “theory of society as it is… dominated at every turn by a concern for the reasonable conditions of life.” The critical theorist thus attempts to understand human things while acknowledging that they themselves have a particular place within them – thus has something at stake in the investigation. For Horkheimer, this opens up the space for the theorist to assume a particular ethical stance: he thinks that our knowledge ought to be guided by a concern for “the rational state of society,” a concern which is “forced upon [us] by the present distress” – whatever that distress might happen to be (certainly there seems no mistaking it today).

The understanding this leads to, of course, falls at least somewhat short of ‘objective’ knowledge – as Horkheimer himself acknowledges. But as there can be no unbiased understanding of human things, we could never hope to obtain this sort of knowledge anyway. Certainly what we can get from critical theory, Horkheimer thinks, is the ability to grasp how things might be different. The traditional theorist approaches society as if the world human beings have created is an alien object, a force of nature that cannot be changed. The critical theorist, by contrast, realizing their own place within the human world, knows that they can act transformatively upon it.

Critical theory, of course, is hardly undemanding. But there is, it seems, no responsible substitute for it today. This is a state of emergency: events right now raise questions about “what is to be done?” which do not fall at all within the norms of liberal democracy as typically understood. When politicians are talking openly about sending in the army, it is hard to believe that people will be able to wait until November to bring about the required change through the ballot box. Something as far-reaching as this crisis in the US takes us all in: even leaving aside the US’s still-predominant international role, the murder of George Floyd has thrown light on racist police violence across the developed world; it is also, of course, not unrelated to the global pandemic which is still ongoing. The present situation thus requires us to consider carefully how exactly we ourselves are, or should be, related to it; what exactly, in this case, justice demands. There is no unbiased perspective on news like this – but it is by practicing critical theory that we might figure out something like the clearest one.

Copied!