Exclusive: Logically Investigation Uncovers QAnon Central Hub Hosting Phishing Scams; Direct Ties to Jim Watkins

Investigation by Nick Backovic and Joe Ondrak.Supporting research by Kristina Gildejeva.

Published: Jun 26, 2020 2:42:23 PM

In the aftermath of Trump’s disastrously underattended rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma and the flooding of racist or pro-police hashtags and communication channels on Twitter, the Internet was awash with proclamations that “zoomers” (members of Gen-Z) were the future – using advanced forms of online activism to thwart Republicans in real-life and the Right-Wing on Twitter. Those reporting on this activism separated this new group of teenage activists into ‘K-pop stans’ and ‘TikTok Teens’ – but they were almost always mentioned in the same breath.

For those used to the disinformation campaigns of Anonymous or worried about Russian bots, this new world of post-Millennial online manipulation might seem dizzying. Fear not, this article is a breakdown of the terms being bandied about, and their implications for future online information manipulation tactics.

Let’s break this one down first. K-pop is South Korean pop music. More specifically, it is a type of pop music centered around groups or musicians referred to as ‘idols’. K-pop is as much its own industry as part of the wider music industry, with companies managing hundreds of acts and running brutally tough academies to find the next new thing to add to their rosters. K-pop fans are known for their highly organized and almost evangelical approach to promoting their favourite band or artist.

A ‘Stan’ is a term for someone who is an obsessive fan, coming from the Eminem song of the same name (despite the oldest Zoomer only being 4 years old when that song was released). The term percolated in black online youth culture before spilling out into the Internet at large.

Interestingly, this etymology suggests that the ‘K-pop stan’ is a distinctly Western fan due to the western etymology of ‘Stan’ itself. While the global reach of social media platforms ensures that digital colloquialisms are unbounded by geography, the behaviour of the ‘stan’ fan is de rigueur for a Korean K-pop fan – the companies managing the bands even attempt to foster it. A devoted fan has a direct impact on the bottom line. There is even a term for obsessive Korean K-pop fans that embody behaviour closer to Eminem’s character; sasaeng fans devote their lives to be noticed by their favourite idol, often resorting to stalking.

The K-pop stan, then, is not necessarily a South Korean fan. As my colleague Edie Miller reported, this assumption resulted in accusations directed at the Democrat Party of ‘foreign collusion’ to upset the Trump rally.

Alongside the K-pop stan is the TikTok Teen. Thankfully this one is far easier to decipher.

These are users of TikTok. The app is wildly popular, but somewhat mystifying if you’re, say, around 30 like myself and haven’t immersed yourself in its fast-paced, hyper-stylized world. The app, owned by ByteDance Ltd. and based in Beijing, was originally centred around lip-syncing to popular songs with a variety of filters. In 2016, it was re-branded and exported worldwide. It operates in a similar way to Vine (RIP), its primary content still being lip-syncs, but also looping videos, calls to action, and strange comedy skits thanks to its powerful editor. Because of all this, the app has a frighteningly quick way of getting ‘challenges’, dances, and other visual participatory memes to trend.

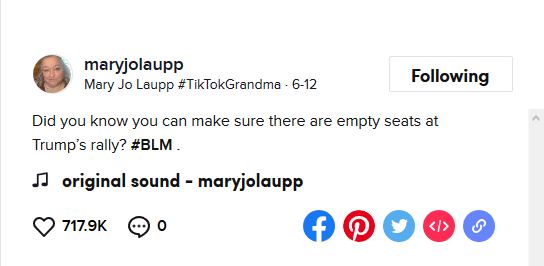

The ‘teen’ side of this label, however, is something of a misnomer. Though 41% of TikTok’s audience is between 16 and 24, the 'TikTok Teen’ as reported on in relation to current events denotes a specific kind of user. This user is politically minded and motivated to do something about it. However, they are not necessarily all ‘teens.’ One user instrumental in organising the disruption to ticket allocation in Tulsa was Mary Jo Laupp, a 51 year old woman who goes by the handle #TikTokGrandma. However, a lot of the active and connected users do skew towards the younger side of the user-base.

So how are these groups connected, and what exactly do they do that sets them apart from previous forms of online activism? It is a combination of sheer numbers and an intimate understanding of the algorithmically-governed content delivery of Web2.0. Unlike millennials, who grew up with an ever-evolving Internet from the Wild West of SomethingAwful to early social media like Bebo and Myspace, Zoomers are natives to Web2.0. This means their understanding of how to do online activism is different.

The aftermath of 4chan and 8chan’s recent disinformation campaign is a good example of this. The average ‘Chan user is older, and operating on the principles of what was novel in a pre-Web2.0 Internet. Primarily, “on the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” – subterfuge and deception through a detachment from one’s real self and their online self. There is a heavy use of sock-puppet accounts to deceive target groups and get them to trend what they want. Deception and trending through memetics is the meeting point of pre-Web2.0 notions of textual selfhood and post-Web2.0 understandings of algorithms and trends.

To counter the 4chan push to get racist and white supremacist hashtags to trend alongside Black Lives Matter, K-pop stans flooded these hashtags with ‘fancams’ – videos of their favourite idols. This is the same technique used and mentioned at the beginning of the article to disrupt other anti-BLM hashtags and crash police calls for incriminating videos during demonstrations. 4chan’s reaction was to create further sock-puppets to re-cast K-pop as racist by getting #kpopstansareoverparty to trend; further deception and trending. This hashtag was also flooded with fancam videos, proving, without any argument, that K-pop stans certainly weren’t over.

This demonstrates a significant difference in the understanding of trending information. For the ‘Chans, the end goal was to trend the hashtags, believing as many do that a trending topic is self-evident. K-pop stans understood that a trending topic is only self-evident as long as the context of what trends is relevant. To drown out white supremacist hashtags or even their own ‘cancelling’ with unabashed fandom is to understand that trending on its own is useless, and that algorithms do not differentiate between genuine uses of a hashtag and something divorced entirely from its original use.

TikTok Teen’s co-ordination in signing-up en masse for Trump’s Tulsa rally similarly show an adept understanding of trending and algorithms. In this case, an avoidance in getting any indication of organising or a movement to trend and alert authorities to their plan. Mary Jo Laupp’s original call to action contains no anti-Trump hashtags. Nor does another video credited with alerting K-pop stans to the call to action. This is all despite hashtags playing a large part in TikTok’s ecosystem. Avoiding any anti-Trump sentiment or hashtags meant that users could organise under the radar to great success.

![Screenshot_2020-06-25 DO Y’ALLS THING I BELIEVE IN YOU #BTS #bangtanboys #bts #btsarmy #army #bighit #bangtan #jungkook #ta[...]](https://www.logically.ai/hubfs/Screenshot_2020-06-25%20DO%20Y%E2%80%99ALLS%20THING%20I%20BELIEVE%20IN%20YOU%20%23BTS%20%23bangtanboys%20%23bts%20%23btsarmy%20%23army%20%23bighit%20%23bangtan%20%23jungkook%20%23ta%5B...%5D.png)

In addition, users would circulate information and delete videos after 24 -48 hours, leaving no sign of planning or a movement to sign up for tickets.

This understanding of how information flows in the algorithmically-governed Web2.0 environment (which is built on the principle to seek trending topics and boost them), is matched by sheer numbers – mostly from K-pop’s deceptively large North American fanbase. The devotion of K-pop stans, usually reserved to elevate groups like BTS to award show glory or sold-out worldwide tours, when redirected for online activism, makes for a digital crowd that 4chan or even some nation states could only dream of.

However, despite an innate awareness of digital information flows, lauding the activist Zoomers as the next thing in online Left-wing activism is a dangerous path to walk. As NYT’s Charlie Warzel warns, Gen-Z is not a homogenous group of BLM-sympathising K-pop loving video producers. TikTok also provides a platform for “Boogaloo Bois” – radical libertarians gunning for a second Civil War in the US. In addition, though the ‘Chans attempt at casting K-pop as racist may have failed, the online right will be finding ways to adapt to Gen-Z’s innate understanding of algorithm manipulation. One concern is that they will adopt the younger generations’ techniques and integrate them into future disinformation and manipulation campaigns. Another more worrying notion is that the right will mobilise the Zoomer’s now-awakened activist streak by couching sinister conspiracies as righteous causes. The resurgence of #pizzagate on Twitter, helped by TikTok, and the younger crowd pushing it is indicative that their methods may be paying off.

Investigation by Nick Backovic and Joe Ondrak.Supporting research by Kristina Gildejeva.

Investigation by Nick Backovic and Joe Ondrak.

As we already know, conspiracy theories can come in various forms and degrees of maliciousness, ranging from the innocuous to the politically motivated and outright dangerous. Some of them may even...

Get the latest fact checks, exclusive content and keep up to date with how Logically are fighting misinformation.

Copied!